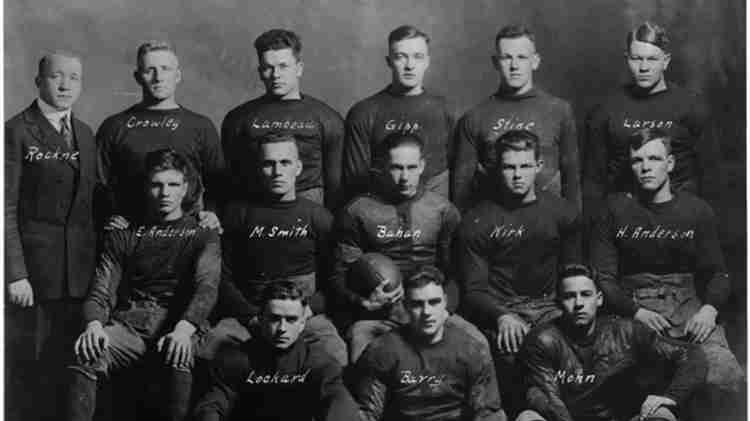

George Gipp (Photo credit: unknown)

No other character in the rich history of Notre Dame football is as renowned, and as difficult to define as the great George Gipp. Amazing athletically, free spirited, enigmatic, his reputation has evolved into legend. Thousands of words have been written about him, books, articles, websites, and he was prominently featured in a Hollywood movie. The problem with defining Gipp is that so much of the available information on the elusive star, conflicts. This two part story, which draws on about a dozen sources and a lifetime of immersion in the Notre Dame football world is an effort to portray the legendary star accurately.

On the gridiron George Gipp was so dominant in his day that according to the legendary sports writer Ring Lardner, “the Notre Dame team seemed to have only one formation and one signal…. line up, pass the ball to Gipp and let him use his own judgment.” Gipp also was skilled in other pursuits, like billiards and poker, and he used both, along with his considerable skills on the gridiron to his advantage during a glorious but short life.

The son of a carpenter, George Gipp was born on February 18, 1895 in the Upper Peninsula village of Laurium, Michigan. A town of about 5,000, Laurium was a bustling town spurred by a copper mining boom in the area.

Growing up Gipp played some football, but it was in other sports that he starred. He attended Calumet High School and led its basketball team to a 24-1 record and its first ever regional championship. On the baseball diamond he made an even bigger mark, as a boy, he was belting long home runs and one season posted a .492 batting average, playing in a league against adults.

Gipp was naturally bright but inattentive to academic matters and he actually never graduated from high school. He was tossed out during his senior year, apparently because he had participated in some sort of vandalism. With few other options available to him, he went to work. Gipp drove a taxi for the next three years, worked as a linesman for a telephone company and became hard scrabble wise in the way of the world. He learned skills he would find to be useful later on including billiards and poker and how to hustle a buck.

Encouraged by his older brother to find a way out of town because George possessed “the brains in the family”, he received a referral from a town friend who had attended Notre Dame and, in the fall of 1916, he was granted a conditional scholarship to attend ND, to play baseball. “Conditional”, due to his lack of a High School diploma.

A strapping 6-2, 185, Gipp arrived in South Bend only to learn that this scholarship, just covered room and board. He needed money.

Having learned how to hustle to support himself during the three years on his own after high school, he went to work in downtown South Bend, as a gambler. His billiards and poker talents became occupations, and he was so good that he soon mostly moved out of the dorms and into one of the downtown hotels, The Oliver. There he resided in relative luxury for the rest of his college days.

One day early in his “conditional” first year, then assistant football coach Knute Rockne was stopped in his tracks at the sight of Gipp, in street shoes, easily punting a football over 60 yards. A conversation ensued and Gipp was convinced to join the football team.

In a non-varsity game against Western St. Normal, during his conditional year, he made the first mark of his free-spirited ways by instead of punting as instructed, dropkicking. The dropkick sailed 62 yards through the uprights to break a tie late in the game. The field goal clinched a victory.

Another act of coach defiance that demonstrates the “Gipp” way, occurred during one of his first ND baseball games. He went to the plate with orders to bunt, but Gipp had other ideas. He saw a pitch he liked, eschewed the bunt order and slugged a home run instead. He later explained this act of defiance by saying that the afternoon was too hot to be running around the bases!

Some coaches would not have tolerated such breaches of orders, even if they resulted in victory. But in Gipp, Rockne sensed a certain athletic genius and he therefore seemed willing to loosen the coaching strings. “He appeared just so sure of himself…. the perfect performer who comes rarely more than once in a generation,” once said Rockne. Another time, in a conversation with an opposing coach, Rockne said of Gipp, “he doesn’t have to be told anything twice. And more often than not he does the correct thing the first time…. for him, football is strictly a game of brains.”

1917 was Jesse Harper’s last season as the ND head Coach, and Gipp, no longer a “conditional” student, made his first appearances for the varsity. In his second, played in game of the season, against South Dakota, Gipp went over 100 yards rushing for the first time and accounted for two touchdowns. One of those he set up with a 40-yard gain on the first play from scrimmage, and for the other he executed a then allowable double pass play that ended in the end zone. He went on to make a mark the next week in a tough 7-2 loss to Army when he punted 11 times. That first season ended early however, when he broke his leg against Morningside after snapping off a 35-yard gain. Despite the season ending injury, Gipp’s magical touch had become apparent.

In 1918 Rockne took over as head coach. Now a sophomore, Gipp was given a full-time role. Over the next three seasons he would average 177 yards of offense in every game he played. And he led the Irish in rushing, passing and scoring each year. To say he was a dominant player, would be understatement.

Due to the Spanish flu pandemic, the 1918 season was shortened to just 6 games, but Gipp’s play was spectacular. He had a 2 TDs, 88 yards rushing and 101 yards passing in a 26-6 pasting of Case Tech, and then 2 more TDs and 119 yards against Wabash.

Against Purdue, Gipp fought off injuries, including a bad ankle and an injury described as a “broken blood vessel”, and seemed to play even stronger. He tallied 137 yards and 2 TDs on the ground, and another on a 22 yard pass he threw. To end the season, the Irish fought to a scoreless tie at Nebraska on a snowy field. Gipp ran for 65 yards and punted 12 times on the day. He also was a contributor defensively as the Irish held the Cornhuskers to an incredible, ZERO first downs. Gipp finished the short season with a 5.5 yard per carry average.

Most of the attention on Gipp’s exploits on the football field focus on his offense, but he was a tremendous defender as well. In those days of single platoon football, according to Rockne, on defense Gipp, “possessed the timing of a tiger in pouncing on his prey”. Rockne also credited his star player with a unique and somewhat incredible distinction, because according to him, “not a single forward pass was ever completed in territory Gipp defended.” While Rockne was known to often speak in hyperbole, his description of Gipp’s defensive prowess should leave little doubt that he was a superb player on both sides of the football.

In 1919 the Irish finished with a perfect 9-0 record, and it was George Gipp who led the way. On the season he averaged 6.9 yards rushing, and accounted for 1446 yards rushing and passing.

The Irish started the season 2-0 with Gipp starring. Next against Nebraska, a team focused on stopping Gipp against all costs, one of Gipp’s teammates converted the winning score, with a 90-yard run off a tricky lateral, from an about to be steamrolled Gipp. Rockne compared the stealthy toss under extreme pressure to a casual, “flip of a cigarette”. In the same game the always looking for an edge Gipp, employed ingenious techniques to burn a few extra seconds off the clock to protect the narrow lead. At one point according to Rockne, Gipp would hold on to defenders on the ground after being tackled thus delaying the process of lining up for the next play. Precious seconds were burned off the clock and the Irish won 14-9.

The 1919 Irish and Gipp continued their roll through the season. In a huge win against Army, Gipp hit seven passes for 115 yards and ran for another 70. Next, the Irish entered the game against 7-0, Purdue. Gipp flexed his passing muscles that day by completing 11-15 for 217 yards and two TDs in route to a 33-13 victory. With the Purdue win and an earlier win over Indiana the Irish had dispatched the other major in state teams and Rockne proclaimed, “supremacy of the State”, and Gipp was looking unstoppable.

The quest for perfection in 1919 concluded with a game against Morningside in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, on a frigid 10-degree day. In the game, Gipp, showed that perhaps he didn’t always have a magic touch but he was always the free spirit. Due to the miserable weather he was not much interested in prolonging the game. The Irish held a 14-6 lead late in the game. Gipp asked of Rockne, “It’s too cold, take me out”. (This from a young man who had grown up on the far northern shores of Lake Superior!) Rockne refused and replied, “one more touchdown”. On the next play, Gipp took a pitch at his own 17, and with determination ripped through the defense all the way down to the three-yard line where he unceremoniously slipped and fell on the frozen ground. On the next play he compounded his miscue by losing a fumble. Gipp therefore had to stay in the game, he then turned dramatically to Rockne on the sideline and casually shrugged his shoulders as if to acknowledge, that he was not quite perfect. But the 1919 team was perfect, as they held on for the win and and finished out the season at 9-0.