In recent days, as citizens marched in cities from coast to coast, coaches from across the nation weighed in on the issue of racism. The Notre Dame coaching staff joined the chorus. Brian Kelly, Muffett McGraw, Niele Ivey, Clark Lea, Tommy Rees, Brian Polian, Terry Joseph, Mike Elston, Del Alexander, Matt Balis and others in the Notre Dame athletic department joined in. Kelly announced the creation of a team “unity council” to be made up of his players and staff. A few weeks later on June 19th, “Juneteenth”, Brian Kelly and his players led and addressed a “peaceful prayer and unity walk” on campus to commemorate the day in 1865 when all slaves were declared free in the State of Texas.

Coaches, at their best can have positive and remarkable impact on their players and others they come in contact with. Indeed, they have been known to change lives. That is what they do. And it goes well beyond the field of play. What has seen in the past several weeks was evidence of coaches recognizing their potential to calm and improve an unsettled world.

I have known and respected many coaches in my life and the “coach chorus” this past week got me wondering about one coach in particular, one who is gone now, but one whom I know that to this day has had a huge and positive impact on the lives of men he coached.

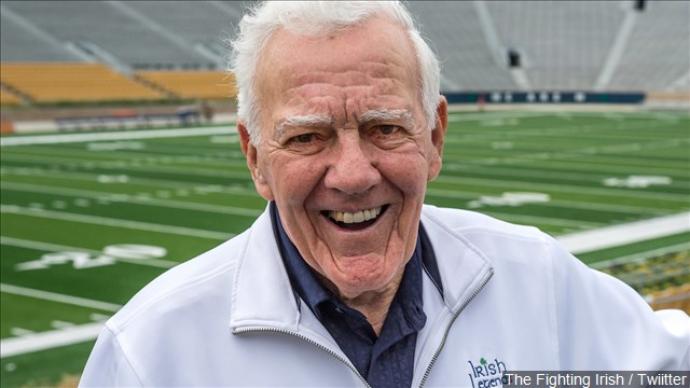

In fact, a revered coach from Notre Dame’s past, seems to have been ahead of his time on social issues relating to equality.

In 1955 Ara Parseghian, the son of Armenian refugees that had escaped genocide in Turkey, was a young head coach at his alma mater, Miami of Ohio. He led Miami that year to a 9-0 record and an offer to play in the Tangerine Bowl, a tremendous accomplishment, particularly in the days before bowl games had proliferated. There was a problem though. The game was to be played in racially segregated Orlando, Florida. The invitation was contingent on Miami leaving its black players at home. Ara, with the support of his school turned the prestigious invitation down.

Meanwhile, in South Bend, slow progress in the area of improving campus diversity was being made. The first African American who enrolled at Notre Dame, was Frazier Thompson in 1944. Thompson graduated in 1947.

In 1953 Wayne Edmonds, a bruising two way lineman out of western Pennsylvania, became the first black player at ND to win a monogram. That season when the Irish played in games at Oklahoma, and North Carolina, Edmonds was not allowed in those places to stay in the team hotel. That same season, Georgia Tech refused to allow Notre Dame to bring any black player to Atlanta to play. The game at Georgia Tech was cancelled and was actually played in South Bend.

Despite some inroads, when Parseghian arrived at Notre Dame in 1964, there were still very few black students on campus. But the combination of a dynamic and charismatic young football coach with a determined University President, Father Theodore Hesburgh, who was serving on the United States Civil Rights Commission, accelerated the pace of progress.

Parseghian recruited many black players and had a reputation for treating them fairly. Among them was Alan Page, Bob Minnix, Clarence Ellis, Thom Gatewood, Luther Bradley, Eric Penick, and Wille and Mike Townsend. At the same time and at Hesburgh’s behest, the University increased scholarships for minorities.

In 1968 Notre Dame reversed its long-held policy of not playing in bowl games. Part of the reason given for that was that the additional revenue would be used to fund minority scholarships.

Between 1969 and 1970 the number of minorities on campus doubled. That freshman class in 1970 had 118 African American members.

Surely if Ara was around today, he would speak out as many other coaches have the last few days, and there is reason to believe that he would speak with authority and empathy.

Frank Pomarico, one of the Captains of Ara’s 1973 national championship team, describes Ara as, “sensitive and fair”. In his book Ara’s Knights, Pomarico talks about Parseghian’s great skills as a communicator, “The lines of communication ran both ways with Ara. He was very clear about what he expected, but he was open to hearing what others had to say.”

According to Pomarico, what Parseghian communicated was often times not even about football but was, “about becoming responsible, to yourself, to you family and your team… he oozed all kinds of information about life, you couldn’t get enough of it.”

In 1967 one of the black players brought in by Ara was a walk on out of the deep south, Greg Blache. Blache hailed from New Orleans, but he suffered an injury that ended his playing career early on. Unable to play, Parseghian asked Blache , to stay on and to help coach the freshman team, which he did. Blache then spent two years as a graduate assistant under Parseghian, and in 1972 Ara made Greg Blache the first ever black assistant coach at Notre Dame.

Blache went on to several other coaching jobs, including a second stint in South Bend under Gerry Faust. Later, he served as the defensive coordinator for the Green Bay Packers, Chicago Bears and then the Washington Redskins.

Blache, retired from football in 2009. In all he coached for 33 years, 22 years in the NFL.

In retirement, Blache lives in the “wilds of Wisconsin”. Now 71, he has never forgotten the lessons he learned from Ara who he refers to as “his second father.” Ara according to Blache, “had great wisdom and great compassion.”

Blache talked about Parseghian’s habit of consuming 4 newspapers every morning before the staff’s 7 AM meetings. “(Ara) was always hungry for knowledge, he was one of the best-read persons anywhere. Politics, social unrest, the Vietnam war, he had insight into all those things. He didn’t shoot from the hip, he researched it.”

Pomarico tells the story of two black players in the early seventies that had been involved in a fight and were suspended from the team. Parseghian showed skill in the way he handled a potentially divisive issue. “Ara was sensitive to the issues of the time but he was just. He called a team meeting and gave a long list of 10 violations they had committed as the reasons why the players had been suspended.”

As it turns out Parseghian had given the suspended players multiple chances before he felt that he had no choice but to remove them from the team. “By the time Ara got to number five on the list, the whole team was united that the suspensions were just,” said Pomarico.

Blache believes the roots of Ara’s principled attitudes came from his parents who had escaped the genocide in Turkey. “He understood what it was for me being black at Notre Dame and in the United States at that time. He knew about persecution, because his parents had come over from Turkey, and he had an understanding that a lot of other people didn’t have.” Blache added to this point by saying, “(Ara) had no tolerance for bigotry and prejudice. He had had the experiences himself, growing up poor, growing up Armenian. He understood.”

Blache, an extremely well accomplished coach in his own right, was a finalist in 2004 to succeed Tyrone Willingham at his beloved alma mater, a job that went to Charlie Weis. Referring to another opportunity he had once had to be a head coach, (an opportunity that he turned down after consulting with Ara), Blache said, “I always thought that you had to be ‘Ara’, to be a head coach. I worked for other great people but I eventually realized there was only one ‘Ara’, he was that unique.”

Part of the fraternity which Pomarico has dubbed, ‘Ara’s Knights’ which includes former players and others who were impacted by Parseghian, both Pomarico and Blache have their own messages for the world in these unsettled times.

When asked what his message to society would be today, Blache said, “I am all for peaceful protests……but I think you have to be judicious in how you protest because people will take what you do and turn it around…. There is a point where you have to realize you need to have a discussion, and more than a discussion you need to come up with some solutions.”

Pomarico also stresses the need for communication in the world today. “Be nice to each other, and give each other the chance to be nice. We need to open up our hearts, we all bleed red”.

Pomarico, the proud grandfather of one year old twins, apparently learned from Ara because he himself is an accomplished communicator. Besides writing Ara’s Knight’s, he has done a weekly radio segment out of Las Vegas on Notre Dame Football since 2002 and currently is working on another radio project called The Kingdom Within, with the goal of assisting people with setting goals to achieve dreams.

As for Blache, he still loves watching the Irish on Saturdays but admits that when things are not going so well at times, its hard sometimes to stay in the room in front of the TV, a trait shared by many coaches, when the game is suddenly out of their control. “I just go out in the yard and work on a project for a bit”, he said.

Like Frank Pomarico, Greg Blache is steadfastly loyal to Ara, and Ara Parseghian, over 60 years ago, was already saying and doing many of the things that coaches in 2020 are calling out for. As a member of Ara’s staff, Blache was privy to much of Ara’s wisdom, “Ara would explain (to his staff) why it was important to have an open mind about things. And he realized that change was necessary. We needed progress to become a more inclusive society.”

A message that would fit right in today.

Ara Parseghian was the head coach at Notre Dame from 1964-1974. He posted a record at ND of 95-17-4 and won national championships in 1966 and 1973. He retired at the age of 51 and never coached again. He passed away on August 2, 2017 at the age of 94.